Episode Transcript

EPISODE FOUR: MYTHMAKING

VENUS WILLIAMS: Episode Four: Mythmaking

Welcome back to Widening the Lens: Photography, Ecology, and the Contemporary Landscape. I’m your host, Venus Williams.

We’re going to start with an exercise.

Close your eyes and picture yourself in a desert—any desert. As long as it isn’t familiar. As long as you wouldn’t necessarily know where you are.

William Fox: When you come over a rise and you see a valley you've never seen before, the first thing you will do is you'll look for something against which you can scale yourself. You want to know that because that will enable you to understand how far away the other side of the valley is because that's your goal is to get across the valley.

VENUS WILLIAMS: This, by the way, is Bill Fox, director of the Center for Art and Environment at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno. He’s also a prolific poet and essayist.

But back to the desert.

William Fox: You're also looking for anything you can hide behind or run to because the thing you're also doing all the time, still yet, is you're looking for those things on four legs that have two eyes, right? They have stereoscopic vision and therefore really good at chasing you down. Those are just things that we do as a creature because they are bred into us out of survival needs. So that's the business of a cognitive transformation. That's where we're already starting to change [space into place].

We're inhabiting it imaginatively. We're not building a house there, but we're definitely checking out to see if there's any shelter along the way.

So I've made it a habit of wandering around the world. Looking at how different kinds of people do this in different places. That's where I can learn the most about human practice, right, of being in the world. And whenever you're trying to examine these mechanisms of how we actually function, it means you have to deal with the myths of the place.

VENUS WILLIAMS: Fox’s work—and curiosity—has taken him to the farthest reaches of the planet to explore, consider, and write about terrain. So he’s thought a lot about this process of turning space into place—and the myths that come from doing so.

Myths and stories can, of course, be productive and destructive. But, as Fox argues, the act of making them out of the things we see and the places we inhabit—or want to inhabit—is something we humans have always done.

William Fox: So the primary factor of the places that I go is that we have made the myth that they are empty the best example is the British encountering Australia. Labeling it terra nullius, you know, the empty land, right? When in fact there have been people there for 50,000 years. That's one thing. Another is that no matter where we are and for hundreds of thousands of years we've developed culture to cope with place. I mean, if you're in the most brutal continent that is inhabited on the planet and you're in Australia, you're an aboriginal person, 50, 60,000 years ago, you've drifted clear across, you know, Southeastern Asia, New Guinea, you've made your way across the Torres Straits by following small islands and you end up in a, you know, what is increasingly an arid place in front of you with plants you don't recognize, animals you don't you don't recognize, more snakes and spiders that are poisonous anywhere else on the planet. How do you survive that?

Well, people came to Australia with a toolkit. They could make fire. They could paint with ochre. They knew how to modify rock shelters, natural ones to enhance their abilities to shelter them. And the most important thing you have to do in that circumstance is remember what you know and pass it on to your children, right? So how do you transfer information from generation to generation? One of the ways it's your song and dance. Song because it's haptic and involves your bare feet and sand, right? You're actually making imprints on the earth. You are talking about that earth. And you're making up stories about the great serpent that comes up out of the ocean and that moves its tail around and creates mountains and then goes back underground, right? And that serpent is still there today, by the way, and you'd be, it ought to be nice to that serpent, pay attention, say its name outside, maybe even sing a song about it every now and then so that the serpent will continue to make the world, right? And those are songs that are sung today that are 50, or 60,000 years old.

So it's a very successful technology, song and dance. The gestures that your feet make on the ground make patterns that you then can put in ochre on your body. And then pretty soon you can put them on walls, right? They become manipulatable, just like any other pieces of data that we have in a computer, right?

Now you've made a system of symbols that you can manipulate. And you teach all of that to your children, and they to their children, and on as many generations as you need to stay alive. So people come into places with very complicated mythologies that are very useful and that are proven to work and help people survive and thrive and so forth. And that's traditional knowledge coming forward into our sphere and it's all the reaction of space and place. It's all that cognitive behavior.

How does photography relate to any of this? So photography in theory, you know, you can freeze the moment. And you can observe, right? And if you do that in a series of photographs, you can create motion that you can stop at will and so forth. The human eye gets ten million bits per second of information, and if the brain tried to process all that information that's coming in down the optic nerve, it would cook itself, it would get so hot. So the brain throws out most of that imagery. What you process is just a tiny subset of what you see. Photography allows us to investigate that process all along the way.

So photography influences us, and by extension our mythmaking, at absolutely an awful lot of levels at which we function since its invention. I mean, within six months of Daguerre releasing the plans for how to make a camera, there are guys sailing up the Nile photographing Egyptian monuments of antiquity. So it's just so fascinating to us that we can participate in the world that way. We can slow it down, we can stop it, we can investigate it, we can move it to another place, look at it at our leisure. So through imaging technologies, we know the world and, and it's become very much part of how we deal with it.

—

William Fox: So if you get ten million bits hitting your eyeball every second and you're throwing most of that away, what on earth are you doing when you're looking at a photograph? Of some place that is an object that represents everything you've ever seen about that place in all the movies and books and everything else?

VENUS WILLIAMS: Many of us would look for the familiar—the things we feel we can grasp, or know; a hint of something we’ve seen before that helps us make other links and connections.

This is where a different kind of mythmaking comes into play.

As photographs start to circulate, first as paper prints and stereographs, then in newspapers, magazines, film, TV, Google, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and now, through deepfakes and AI tools like Dall-E or Midjourney, it can be difficult to know what stories or myths we’re being exposed to.

But Bill Fox thinks there could be a way out.

William Fox: Things are what they are. And we develop technologies that once we develop them, and we will keep developing them because that's what we do—they're going to get used. And we're going to use them again and again until we force ourselves to stop if it's not good for us. That's the history of nuclear testing, right. I think it's also the history of climate change now. We just get locked into kind of modes of seeing and believing and acting. And you have to force yourself to stop from using things that have the power to cause harm. And the way you do that is you see yourself doing it.

Those things exercise an enormous amount of willpower. And the only way you have the willpower is if you know that challenge and opportunity exists. And the only way you can do that is if you can see yourself acting. And so that's what art helps us do, right? Artists are really skilled at helping us jump out of the loops.

—

VENUS WILLIAM: Now, back to the American West—the site of so many of our conversations to this point and a mythology so pervasive it’s basically cliché.

The ability to manipulate space in a photograph—to frame it, to stop time exactly where you want it, to add, to excise—all of this is key when we think about the kind of mythmaking photography has perpetuated throughout its history. And how it works in tandem with the cognitive process of turning space into place Fox described.

Because as we talked about earlier in this series, when it comes to mythmaking and photographing the land, photography also brought with it the myth of objectivity—the idea that a photograph of a place must, by virtue of its technological nature, depict the reality of that place.

A myth that led to many other myths. Myths like:

William Fox: There’s a lot of empty land and we can do anything we want to it, because nobody was ever here before us, and anything that we do will succeed, and we'll make money while doing it. That's the nutshell, right? Of our kind of self delusion that imaging and photography are used to buttress up.

VENUS WILLIAMS: Indeed, we see a host of other myths come out of the myth of emptiness. Myths about indigenous people as quote “savage” or, later, as eradicated. Myths ignoring or revising certain histories. Myths about pioneerism and its infallibility. Myths about cowboys and sheriffs patrolling wild lands, wrangling animals, and bad guys into submission before scooping up their damsels in distress. Myths that continued to take shape as early photographs became early films, which then gave way to television shows and ads rife with a certain kind of imagery—mostly about a certain kind of man—that still circulates today.

Vintage film excerpt (American Cowboy, 1950)

Artists, of course, are still grappling with these myths too. Some by countering them, some by dismantling them, and some by making new myths of their own.

—

Mark Armijo McKnight: My name is Mark Armijo McKnight. I'm an artist and educator. I'm currently an assistant professor of expanded photography at Rutgers University. And I'm interested in the body, queerness, mythopoetics and, the archetypal and probably most often, the ways in which those things intersect with, the quote unquote natural world or the landscape.

Sam Contis: I'm Sam Contis. I'm an artist. I think I'm drawn to the body in flux, both in motion through the landscape and also through transitional states of identity. I think that's a theme that runs through my work.

NARRATION: Both McKnight and Contis confront the mythic in their work, some of which is literally rooted in the American West. But they also share a passion for photography as a particular artistic tool and medium.

Mark Armijo McKnight: Something I really respond to and that I've worked towards in my own photographs is almost like a centrifugal sort of force in the pictures that suggest some kind of like antecedent to the picture, like time really sort of stands still, but there's like a suggestion of movement.

I think that something that's really important in both of our works, to my mind, is the sort of suggestive capacity of the image. Because it's a static image, the audience or viewer of a given photograph has to sort of project onto the image what happens next, in a way that feels maybe different from some of our peers who work with photography and are more interested in classic forms of portraiture, for example.

Sam Contis: Yeah. I agree with what you're saying there. But I was also thinking as you were talking, you know, I think part of what I love about photography and what it enables me to do in a way that's different than if I was working in other mediums is that photography is something that keeps me immersed in the world, and allows me entrance into worlds that I might not otherwise be invited into, and lets me stay in those worlds for quite a long time.

And allows me to keep looking at the world, which is what, ultimately, I'm really drawn to. I can invent things within that world too through photography, but it keeps bringing me back to looking and seeing and trying to understand and using the camera as a tool to understand the place that I find myself in. And I think there's something very particular about the way photography can do that and the relationships that can form between you and a place or any sort of subject matter that you're looking at.

VENUS WILLIAMS: McKnight and Contis are also artists who have thought a lot about the history of photography.

Mark Armijo McKnight: There's some traditions in photography that were really revered when I was an undergraduate that I felt beholden to and also really at odds with. In some ways, I'm really indebted to a lot of modernist photography and have a quote straight photographic approach. And like for any would-be listeners who might not be familiar, straight photography is a term for images that are made to depict a given scene in sharp focus and detailed. It's often associated with modernist photography, which was this reaction to the soft focus, enigmatic, pictorialist photographs of the early 1900s. But I've always found it funny that this word, quote, straight gets used to describe a form of photography that has so many associations not only with words like purity and fidelity and objectivity, but also for the most part, white heterosexual masculinity.

I think the inherent implications that objectivity is possible at all in photography is absurd and that some subjectivities, in this case, white, masculine, heterosexual ones, the suggestion that they can be objective, I think became a kind of problem for me at a certain point. To be clear, I have bigger fish to fry than modernist photography, and this isn't the reason I get up in the morning and choose to be an artist, but I definitely take a sly pleasure in queering so-called straight photography, and I like to imagine that I'm in some way helping to maybe disrupt a predominant historical narrative and offer something that underscores or celebrates difference and my subjectivity rather than trying to foreclose anything.

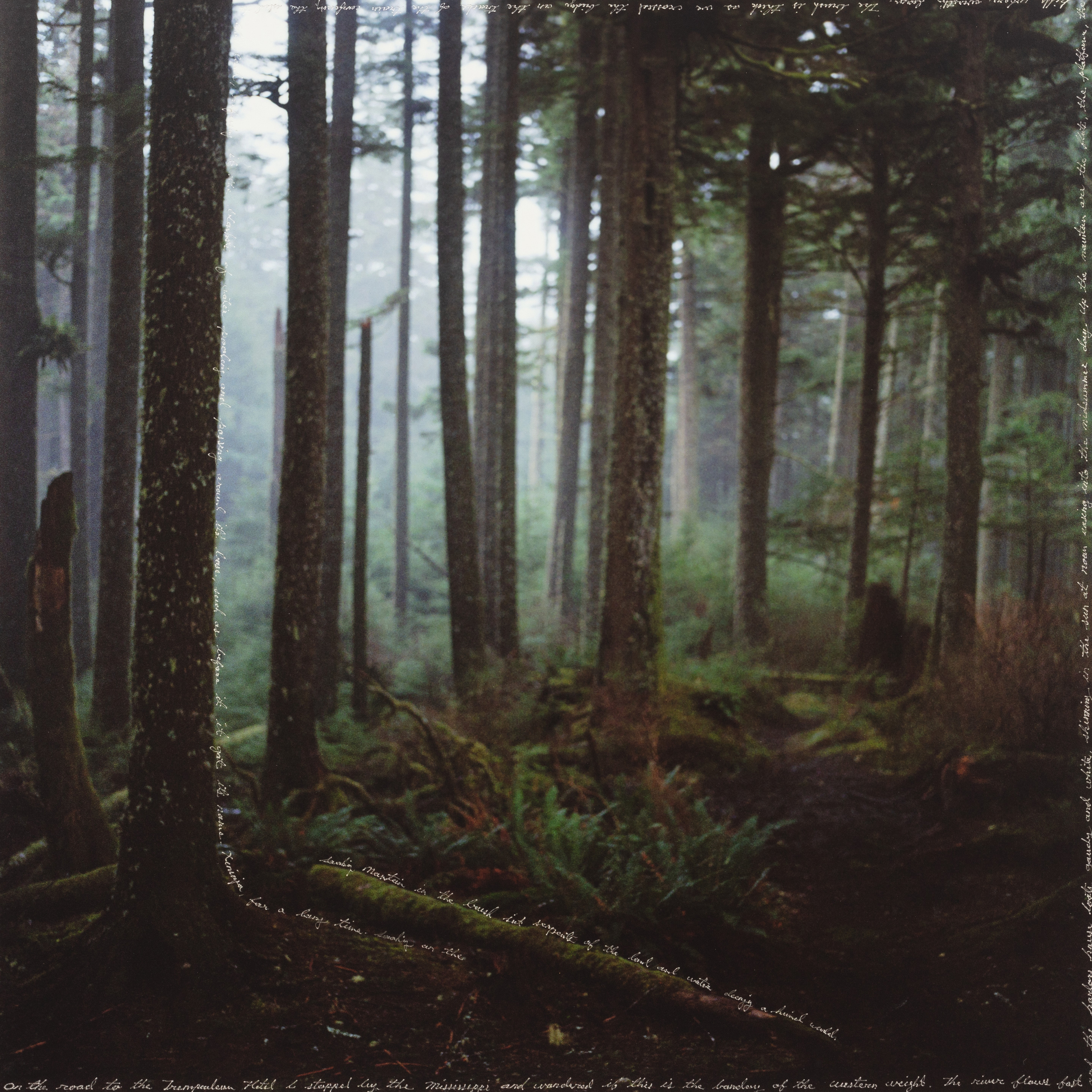

I'm really interested in opening things up and my investment is really in mystery and poetry and I think one of the ways I arrived there is through printing. Like I'm an educator and, I think sometimes to the frustration and insanity of my students, I'm, like, really reticent to say that there is a right way to print a photograph. I make unconventionally dark prints and I underexpose negatives really with the intention of creating these sort of shadowy psychological spaces in which a viewer might get lost, or project, or speculate, or experience.

And, for me, the prints are a way of almost asserting the inherent limitations of the medium, and asserting that an image can't give you everything, and that you really have to bring yourself and your subjectivity to it.

I don't believe in an idea of universal beauty, but I do believe that beauty is universal in that it's this thing that we can all aspire to. But these notions around universal beauty that I think are really put forward in modernist photography, and I mean, I could go on and on also about the relationship to landscape and beauty and also ownership, I'm always thinking about the Watkins, Best General View

VENUS WILLIAMS: This is an iconic photograph Carleton Watkins took of the Yosemite Valley in 1866, from what he called quote “the Best General View”: high up on a mountaintop, literally surveying the land beyond and below.

…and the ways in which early landscape photography, particularly in the United States, even the vantage point suggests a kind of ownership that there's something to be arrested or contained or dominated in the landscape. I'm just really diametrically opposed to viewing the natural world that way. The landscape for me is a place to get lost. It's not something to control or own.

Sam Contis: It's something I think about a lot and I think Deep Springs was really a place where I started to think about this history. And think about, you know, you just mentioned Watkins and the picture Best General View, being high on a mountaintop and that perspective that that is the best view and this idea of surveying or, as you said, dominating or a kind of conquering of this landscape and I think my work is always about trying to push back against a lot of these dominant narratives that have emerged from the beginning of photography, and they continue to exist even now. And so trying to find space to break apart some of these mythologies and try to build new ones in place.

—

Sam Contis: I grew up on the East Coast. I grew up in Pennsylvania, but I started making the work Deep Springs shortly after I moved to California, which was in 2012. Prior to making this work, I'd been thinking about some of the early survey teams traveling across the American West, documenting the landscape, and making pictures. I was thinking about the camera's invention, too, at this time, and the ability to fix an image on a plate and, you know, that that was what gave some of the earliest photographers people like Timothy O'Sullivan or people like Carleton Watkins, you know, it gave them the ability to measure and document these Western spaces. And so I was interested in the fact that these images weren't just a way of surveying the land, but they were also working to create new narratives around this landscape. And so when I moved to California, I had a lot of these early pictures in my mind and instead of trying to emulate these pictures, which are, again, you know, they're often made from the perspectives of someone standing on a mountaintop, I wanted to make pictures that took you physically closer to the landscape.

For me, this was connected to making images that didn't feel stuck in the faraway past but but I wanted to try to make pictures that felt more alive and more immediate and and more present. And so I was trying to get away from these early images of the Western landscape and beyond the pictures that we've come to know through advertising or TV or film. They're so powerful, these images, and they can really continue to condition the way we think about this environment. So when I moved West, I was really looking for a way to engage with the mythology and the iconography around the American West in a more personal way.

VENUS WILLIAMS: Soon after her move to California, Contis came upon Deep Springs College, which is located near the California-Nevada border, just east of the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

Sam Contis: You know, it was in early 2013 actually that I found myself on this really long drive through California and I was driving through a remote valley in the high desert on the eastern side of the Sierras. And it's in this valley that there is a college that actually I had been hearing about for many years. This college was one of the last all-male colleges in the United States at the time. And so I visited, not with any particular intention, just, just really because I was curious. And then I ended up returning to this place to make photographs for almost five years.

I think one thing to say about the school is that, you know, for the five years that I was making pictures it was open to anyone who identified as male, but the school did go co-ed in 2019. But part of what drew me there, I think both to the college and maybe more generally to the space of the American West was I felt a strong desire to inhabit a landscape or a place that in some ways felt off limits to me. As a woman making work in a traditionally all male space, I could say, you know, the space of the college, but more broadly, I'm thinking about the space of the Western landscape, I really wanted to try to look at certain traditional notions of gender, especially as they relate to the ways we might think about the environment. So I wanted to try to make work that might suggest another side to our both, like, historical and present reality. In particular, a kind of experience of gender that is more nuanced and more open to ambiguity than these pictures we've come to know or this idea that we've been, in a way, like conditioned to believe in.

One example, there's a black and white picture of the side of a horse, and it's a horse that John Wayne or the Marlboro Man could be riding, but I get really close to that horse so you don't see the entire body of the horse, you just see this piece of it. And in this abstracted way, it starts to feel like a kind of map or a topography. You see the land, like you see the sun and the leaves of a tree drawn on the body of this horse. And so, in a way, like, making this kind of picture is like presenting a new kind of topography or a new kind of a landscape through the body of this animal.

So In a picture like that, I'm trying to reference this historical framework, but then also push back against that. By using some of those ideas that are related to that imagery, but then presenting it in a new way.

VENUS WILLIAMS: Other photographs in Deep Springs include images of the land itself, viewed less from Watkins’s “Best General View” up-high, than from vantage points within the crags and valleys themselves. We also see cowboys—real cowboys. Strong, young men from diverse backgrounds tending to the farm and the land alongside their academic pursuits.

There’s an intimacy and tenderness in how Contis photographed them. Instead of a rugged exterior shell we see a more sensual beauty in their musculature rising and falling in shadow; we see the softness of their bodies resting in the sun. These young men come across as strong but also gentle—gentle toward the land, toward its creatures, and toward each other. Archival images Contis found on-site at the college confirm that this seems to have always been the case.

Here’s Contis again:

Sam Contis: A few things to say about the college are: it's a two-year college, and it's entirely tuition free. It's actually very hard to get into because it's very small. There are 25 to 30 students in total at any time. It has a very rigorous academic program, and I'd say that a lot of students are drawn to the college because they're interested in alternative forms of education. The school itself emphasizes self-governance and manual labor. So the students work a cattle ranch and an alfalfa farm, and of course they do other less glamorous jobs too. But I was interested in this place, um, because of some of the labor that they do in the landscape and the way they do come to inhabit the persona of this cowboy. And so in a lot of the pictures, I'm showing fragments of bodies and landscapes to try to dismantle the existing mythology and build something of my own in this place.

Another thing I wanted to do in the work was call attention to just how full of life this desert landscape is, despite the fact that it's a desert. And so I really wanted to try to find a way for my pictures to speak to that idea that this isn't a static landscape fixed another time, it's a landscape that's alive, that's malleable. It's a landscape that I really saw to be constantly changing. So there's another picture where there's a young man, he's been planting in the garden and you can see the dirt caked around his fingers and he's gently holding a leaf with a caterpillar on it. So that caterpillar, you know, was an example of the way in which I'm looking to constantly nod to the transformation that is occurring, both in the landscape itself and in the bodies that inhabit the landscape too.

VENUS WILLIAMS: Like Contis, McKnight wanted to point to misconceptions about the American West by depicting a place that is full of life—its cycles and its desires.

In his series Hunger for the Absolute, he photographed nude male figures communing with nature and each other in a high desert landscape. The black-and-white images depict bodies, trees, and rocky terrain all sculpted by natural light. The bodies are enmeshed as they perform tender but also graphic acts. Trees stand tall and stately in some images; in others, they lie corpse-like, overturned. The curves of hills and valleys suggest the curves of bodies. And wildflowers imprint themselves as shadows on two lovers’ backs.

Here’s McKnight:

Mark Armijo McKnight: I was born and raised on the high desert periphery of Los Angeles, which is where I made all the photographs. So it's really personal to me and my relationship with it is decades long and ongoing. People often mischaracterize the high desert as sort of like desolate or empty or blank. And in actuality, it's none of those things. By all appearances, it's austere and, and beautifully so, but it's also really rich. And I think that's maybe one of the things I find really attractive about it. It's a landscape that keeps its cards close.

One of the motivations for the work was to populate the landscape of my childhood with the kinds of bodies I wish had been available to me, so queer subjects. In that way, I'll echo a writer friend who wrote an essay for the accompanying book where he calls it a utopic redemption of the past and goes on to say that that's a sort of strategy for queer artists and image makers. And I'll just really wholeheartedly agree.

VENUS WILLIAMS: That writer is novelist Garth Greenwell. And part of what he’s getting at here goes back to McKnight’s earlier comments about modernism. Because alongside what’s new and maybe even radical, there is something incredibly classic about the photographs in this series—something that even harkens back to mid-20th-century photographers like Edward Weston, whose crisp black and white photographs of everything from the Yosemite Valley to common vegetables to the female (and always the female…) nude are similarly sensual and lush.

Mark Armijo McKnight: I think when I started the project, I didn't entirely know that that's what I was doing, but I think as I was reaching the end, I was well aware there was something really redemptive or cathartic or healing about making this work.

Previous to the work that would be known as Hunger for the Absolute or Heaven is a Prison, I was describing human subjects that were ambiguously suggestive of my desire. And of course that was purposeful, but around the time I started making this work, I was asking myself a lot of questions which were namely focused on my own hesitation to depict the act of sex itself. I really wanted to know what the root of my own reluctance was, and very early on this question of pornography came up, which just begot more questions, right? Like what constitutes quote fine art and what constitutes quote pornography? And why are these designations still mutually exclusive? And, you know, more importantly, who decided that sex was not meaningful? Or why is an intellectual response to an artwork privileged over an unconscious or a somatic one? For instance, arousal. In some ways that's like an ideal response to me now with this work.

It's not that this project was anti-intellectual. But I really wanted to insist on the lyrical beauty of these bodies and these acts, which are really subjects that have not historically been depicted in this way with grace and beauty and care. That was really, really important to me.

Sam Contis: You know, I think that's something that we're both really interested in, is this relationship between body and landscape and how they're reflected in each other, how the body is reflected in the land and the land is reflected in the body. And also I was thinking that we're both, we're both looking at the landscape and bodies with a very strong sense of desire, I'd say. For me, you know, desire is something that's very important in the way I make pictures. But also I think about desire or desire is, is very much related to, to intimacy and to vulnerability. And when I look at your pictures, I think about those things a lot.

Mark Armijo McKnight: Yeah. I mean, what is important, or I'm really excited about the prospect of leaving desire unrequited, and that's almost more powerful than a literal or psychological consummation or something—the having of the thing.

Sometimes the scale of the landscape is really large and the subjects feel so small against it and those images were made on a, on a large format view camera for the most part. And then there are these other images that were shot on a six by seven with a macro lens. So that you're kind of thrown into the chaos and hunger of desire and then you're kind of forced back out so you can see how small, maybe, that desire is relative to the scale of the landscape or something. But also I was really interested in using these images of empty landscapes to also suggest a kind of unrequited desire or to suggest the landscape as a kind of third party to this very literal intimacy that I'm describing, which is also why the photographs rarely confer a horizon.

It forces a claustrophobic intimacy with the terrestrial while paradoxically suggesting that this landscape extends infinitely into a kind of Eden-esque otherworld, which is like another reason why the desert landscape was so crucial to me.

Getting back to this idea of letting something remain unrequited, I really wanted the subjects In this work to feel like that, like they're at arm's length as though we, the viewer, are sort of eternally on the cusp of recognition, that the images and the subjects within them are sort of refusing us in some way.

—

Sam Contis: I want my work to be open to different readings. And in that way, a lot of my practice as an artist is about looking at a subject repeatedly looking at it again and again, and from different perspectives.

Overpass is a series of works, it's also a monograph of the same name that was published by Aperture. And in this project, I'm interested in the implied presence of the body in the landscape. So you actually, you don't see figures in the landscape, in this work in the way that you do Deep Springs, for example.

This work was made out walking in the north of England, where across the entire UK, there's a vast network of public footpaths. And these footpaths, they allow you to walk across privately owned land. It's a remarkable thing, particularly to me from an American perspective, the idea that you can walk across privately owned land was, you know, quite shocking the first time I experienced it.

But anytime you're out walking and you encounter a wall or a fence along these public footpaths, there's usually a gate or there's something called a stile. And a stile is a structure that allows you to climb over the wall or fence that might be in your way that might be impeding your movement.

So essentially a stile is something that helps you to keep moving and sometimes these stiles are very simple structures and sometimes they're a bit more complex. So you can, you can see these different kinds of forms in the photographs. They feel like these found sculptural forms in the landscape that have a practical sort of architecture to them. I've been looking at stiles for a long time before I actually thought about making pictures of them. Um, but the idea for the project started to come into focus around 2016. I was thinking at that time, I was thinking of the anti immigration and far right rhetoric that surrounded, for example, the Brexit vote and Trump, really, you know, I was thinking in particular of Trump's constant invocation of the border wall and I started thinking of the stiles as ways of representing an opposing idea. These structures, they're designed for facilitating movement. You know, they're not trying to prevent movement. But of course, like, they also imply this system of borders and barriers, right? Like a stile, a stile doesn't exist without a fence or a wall.

So I think the more we look at the land and the more we look at it through different lenses, the more complexity is introduced into the landscape and into our way of thinking about it. And so by introducing greater complexity into our understanding of a place, we start to see greater possibilities in that landscape too. So I think in that way it might actually start to reflect the sort of environments that we want to inhabit.

Mark Armijo McKnight: I think for me it's about unity. It's about sort of collapsing the distinction between, between us and quote unquote landscape, which is a kind of manmade construction as an idea. In some ways, collapsing those distinctions visually is essential for me. It's also towards metaphor, right? Like, my medium isn't language, so I'm not drawing a parallel linguistically between something in the landscape and the object of my desire and, or affection. I have to do that using the camera so that you understand what kinds of parallels I'm seeing in the world. And I think the freedom of this landscape permits the freedom of these men to really revel in each other. And in some way, I think, It addresses maybe some of these larger questions that I've internalized around extraction and ownership as someone who has been thinking about those things and also studying and reflecting on landscape in art as a subject really, since my early twenties.

—

VENUS WILLIAMS: Let’s go back once more to the myth of the empty—the “big myth,” as far as the American West is concerned. A myth that continues to be built on the foundation of other erasures, as certain histories are still ignored or sidelined to make room for other narratives, other people.

Which brings us to an artist who’s working to counter myths of the West. And combine more ancient modes of storytelling with imaging the land to bring critical histories to light.

Raven Chacon: I'm Raven Chacon. I'm a composer and artist based in Hudson Valley, New York, and Albuquerque, New Mexico. I mean almost all my work starts off as music compositions. I've made music my whole life, and it's ongoing research and ongoing collaboration with other people, other artists, other musicians. But somewhere in there it started branching out into other mediums, into making work for video, making more sculptural work, making installation environments. For me, it's been an opportunity to talk about places and sites, especially where I come from, the Southwest U.S., and the history of those places, and also the more kind of recent topics that are concerns of those who live and steward the lands of these places.

VENUS WILLIAMS: In addition to the videos and installations he shows in galleries and museums, Chacon’s repertoire has included operas and orchestral works, like the Pulitzer Prize-winning Voiceless Mass from 2021:

–VOICELESS MASS EXCERPT–

By combining elements of classical composition with experimental noise, Chacon confronts histories of displacement and violence embedded in American landscape, toggling between dissonance and harmony.

This sonic tension also evokes a cognitive dissonance that arises when pervasive myths obscure painful histories—a concern Chacon carries into his video art.

Raven Chacon: Making video that was an extension of the music compositions that I was making, allowed me to do a few things. If I was writing a composition about Fort Sumner, which is the place where the U.S. government took our people and made us live in a concentration camp and tried to kill us. Well, what happens if we film in these places? What happens if we take the performance of the song that is the composition and sing that song in that place?

And so video allows one to do that, to move around to these places, to capture the outdoors, to capture the light, capture the morning, capture the night. And I always stumble upon the right word because I don't want to say capture, capture the environment, capture the sounds, maybe gathering the places I wanted to collaborate with, that I wanted to speak to, that I wanted to learn from.

So video did become an early practice, but I was more concerned, in both audio and video, in the lack of fidelity, maybe the misrepresentation of these places.

The other thing I want to say about that is that it can misrepresent a landscape today by making one believe that there are no encroachments. Obviously there's been uranium mining, coal mining in our lands, and we often don't see that.

—

Raven Chacon: A lot of my video works that are presented in installations, they might not have a clear beginning or end. They will run on a loop, in a cycle. And so Three Songs works in the same way, where if you're encountering this exhibition, which should be in a darkroom for, for the best video presentation. You would see a woman singing a song in her indigenous language and using a snare drum to sing this song. And the video will show subtitles of what is being said in English. And these subtitles will tell the story of the place where the performance is taken.

So there's a performance by a musician named Sage Bond, who's Diné. And she is singing a song of the event I was telling earlier about when Kit Carson removed Diné people and forced them to live at Fort Sumner in a concentration camp, which was 300 miles away from where everybody else was living in a place that was a completely brutal desert, no water and no environment to grow any kind of food.

So the song that she is singing is telling that story. Meanwhile, she is in a landscape where there is coal mining, the Peabody Coal Conveyor Belt, which runs between Tuba City, Arizona, and Kayenta Monument Valley. And so this cycles through three different songs that talk of massacres and displacement and forced migration, while each being sung in a landscape that is traditional homelands but are also facing a current encroachment, whether it's the coal mine or a hydroelectric dam or the reservation itself.

VENUS WILLIAMS: The first image we see in Three Songs is a wide shot of Bond standing in a field at what looks to be shortly after sunrise. She is frame left; a massive coal silo and conveyer belt stands behind her to the right. She is dressed in black and beating a snare drum cradled in her arm.

Raven Chacon: The snare drum is a symbol of a military instrument. It was the instrument of the U.S. Calvary. It was a signal that you were being raided upon by this army of the federal government. At the same time, these songs are talking about some very distressing topics of our own attempted murder. And so I wanted to think of a drum that could take on that burden. I also like to think that, you know, in some, some universes, these women were out walking in their homelands or in their new homelands and stumbled upon a snare drum sticking half out of the ground and picked it up and started telling a story.

—THREE SONGS EXCERPT—

VENUS WILLIAMS: There’s always something at stake in mythmaking and mythbreaking. In Chacon’s case, he feels a great responsibility toward his own people and toward other communities, both past and present.

Raven Chacon: There's always a concern of being too anthropological or extractive of even yourself, of where you come from, of telling a story that you might even be removed from whether that was a forcible removal or something else.

The goal is not always to share everything. And so I think it becomes a very first-person dilemma when thinking of the work I'm going to make, of thinking of the tools I'm going to use, and then extending that to any collaborators that are going to be involved.

I think there's a responsibility there of understanding what it is you're going to be gathering. And how that's either going to be a representation or how that's going to be a mutual disruption.

VENUS WILLIAMS: The English translation of the song you’ve just heard Sage Bond sing in Chacon’s, Three Songs, is as follows:

Over there, at Fort Sumner

we marched, dying of thirst

the water is black

Coward men waited

until we were alone with our babies

Our sheep

killed in their sleep

The rocks are black

Choking us now

blackened smoke

rising out of the earth

The water poisoned,

the land now dying of thirst

In darkness, they were born

I watch again

I watch again

—

VENUS WILLIAMS: Thank you Bill Fox, Mark Armijo McKnight, Sam Contis, Raven Chacon, and Sage Bond. Fox’s books include Playa Works: The Myth of the Empty and The Void, The Grid & The Sign: Traversing the Great Basin, both from University of Nevada Press and both under the byline William L. Fox.

We discussed Contis’s series Deep Springs, which also exists as a publication from MACK; and McKnights’s Hunger for the Absolute, which is collected in a book called Heaven is a Prison by Loose Joints Publishing, though listeners should be advised that McKnight’s work does contain sexually graphic content.

You also heard an excerpt from Raven Chacon’s Voiceless Mass, his Pulitzer Prize-winning 2021 commission from Present Music, the Wisconsin Conference of the United Church of Christ, and Plymouth Church UCC. And from his video installation, Three Songs, featuring singer, Sage Bond.

Widening the Lens: Photography, Ecology, and the Contemporary Landscape is a production of the Hillman Photography Initiative at Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh. For more information on the people and ideas featured in this episode, please visit carnegieart.org/podcast.

I’m Venus Williams. Thanks for listening.

###