Episode Transcript

EPISODE FIVE: ATTACHMENT

VENUS WILLIAMS: Episode Five: Attachment.

Saretta Morgan: “The Corpse at Stake was a Dream We Felt Inside Of,” by Saretta Morgan. That we arrived was not an explanation, not even through erogenous terms. To the question that bore a horizontal appearance but no scent or other indication or contraindication of the consequences inherited from feeling this way.

Feeling (inside) exuberant. Invaginated. Turned around by the same hands (inside) again. We wanted to know what it meant to be constituted through the particular exclusion of every other yield, or open pit. Yes, we came when called to beauty. Then, asked who were we while looking into the eyes of our interior stranger.

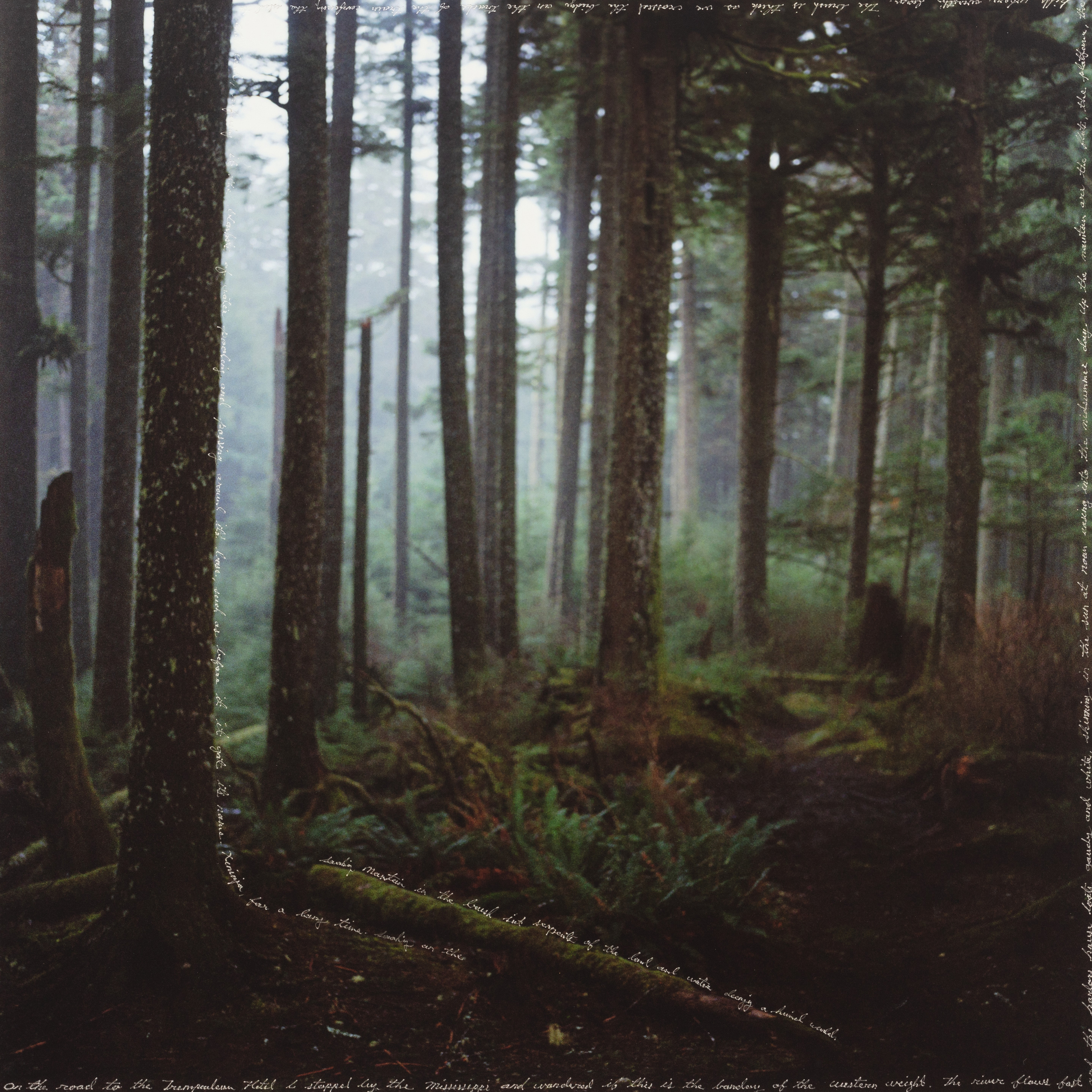

The teary face that neither came nor went yet appeared at the edge we held on to. || Image Caption: That the territory is shared extends thresholds of presence. What exposes the image disorients the horizon while remaining perfectly at ease. End caption||

VENUS WILLIAMS: I’m Venus Williams. Welcome back to Widening the Lens: Photography, Ecology, and the Contemporary Landscape.

And that was Saretta Morgan, reading from her poem, “The Corpse at Stake was a Dream We Felt Inside Of,” a Carnegie Museum of Art commission.

The image caption Morgan read sits below an archival photograph of a path winding through rocky terrain. It was taken in December 1942 for the Farm Security Administration, and sits in the Library of Congress’s Office of War Information Collection.

Here she is again, with another excerpt:

Saretta Morgan: This is what you need to know. The organic disruption of order is a concentrated beast. In the dream we gorged. Were milked. The consequences weren't immediately visible.

Turned out by it, we said, gently now. || In the dream, we approached the border where life was no longer possible. Dredging the river, slipped from the caravan, one environment extruding life from the next. Proliferating terms from our rough understanding of what emerged in the physical development of this type of country. An indicator species.

A concentrated beast pointing toward the health of a question. Land is not a metaphor. The question was always: which corpse will constitute an environment today?

|| Image caption: Twenty miles into the state border. Extracting generative terms from the interior state, from the arbitrary nature. A membrane that bleeds.

VENUS WILLIAMS: This image was taken earlier, in 1928. It depicts Black soldiers on horseback, entering an historic stable structure at a military installation near the Arizona-Mexico border.

–

VENUS WILLIAMS: Saretta Morgan is a poet currently based in Atlanta, Georgia, but she spent time living near the Arizona-Mexico border where, in addition to her literary work and teaching, she organized with a grassroots humanitarian aid organization helping migrants called No More Deaths.

Saretta Morgan: My work typically pays attention to how intimacies emerge in the wake of state-scale violence and I think also about alienation as a consistent byproduct of such violence. And for that reason, I often write from a first person plural perspective. I'm consistently interested in what it means to refuse being alone or understanding yourself as not being constantly attached to others.

There's a writer that I look to a lot named Suzanne Césaire, and her husband, Aimé Césaire, is very well known. Suzanne published very little. Her publishing career pretty much ended at the onset of their marriage when they began having children, when his political career took off, et cetera. But she has this piece that she published in the early forties, “The Malaise of Civilization,” where she talks about the need for oppressed people to develop an ideological posture that reflects their nature as opposed to mimicking Western knowledge production.

VENUS WILLIAMS: In this essay Morgan is referencing, Suzanne Césaire writes about the formerly enslaved population of her home-island of Martinique, a former French colony, and current French territory; the problem of equating liberation with assimilation; and the imperative to look instead to, as Césaire puts it, “the long lasting and fruitful harmony of humankind and soil.”

Saretta Morgan: And I think for me, that says that at a very fundamental level, we have to have a view of the world and ourselves in it. Like, that's the foundation. And, you know, being of African diaspora, descended from enslaved Africans, our worldviews were lost. Or, I shouldn't say they were lost, they were taken. And so I think to be able to say, this is the landscape, and to elaborate on that from a place of subconscious, as opposed to regurgitating what a formal study in geology might ask you to believe about what it is that you're seeing, and how it relates to you is very critical to the project of liberation and I think also just to existing on a daily basis with capacity to love and respect yourself.

VENUS WILLIAMS: What Morgan and Césaire are talking about here is using our bodily attachments to land—traumatic as some of them may be—as inspiration for creative thinking. It’s a call to action for oppressed peoples in particular to find new ways of depicting themselves and their lost or adopted lands, drawing on a deeper connection between body and place.

Photography can be a tool to visualize bodily attachments to land—and to resist the attachments and associations imposed by others.

That’s what we’ll be talking about today.

So let’s get back to Morgan’s new work, which, as you heard in those first excerpts, has a photographic element to it, too.

Saretta Morgan: “The Corpse at Stake was a Dream we Felt Inside of” is a poem written in four sections. All four from the same first person plural perspective, sort of an unnamed chorus that's moving through a landscape, and the language is interrupted by archival photos depicting rural Arizona around the 1940s, and they’re landscape views as well as depictions of early black settlers in those spaces.

I wrote this as I was leaving Arizona—I've been living in the well between the Mojave and Sonoran deserts for a little over five years. And one thing I did was I went back to some photo archives that I looked at when I first moved to Arizona. And I was really thinking about, one, I was just really shocked. I don't know why I was shocked, but I was very shocked at the lack of Black presence in the Phoenix area in particular.

And so I was doing research trying to find images of early Black settlers I was also very interested in trying to find images that reflected Black and Indigenous encounters, whether amorous or otherwise. And I couldn't find that. And when I think about it, like, later, I'm like, why would that photo exist? Like, who would preserve it at that time? But what I was really interested in was the language around them, the image captions. In the poem, there are phrases that repeat, and most of those are derived from image captions from those photos.

VENUS WILLIAMS: Morgan was looking specifically at photographs taken for the U.S. Farm Security Administration, or FSA, around the time of the Great Depression and in the run-up to World War II, when they sent photographers West to document the landscape and different mining and agricultural endeavors. One of the phrases she kept seeing in the photo captions for these images was “this type” or “this kind of country.”

Saretta Morgan: They would take these landscape photos and say, ‘this is the kind of country that exists, you know, around Kingston, Arizona, where mining is fueling our war efforts, blah, blah, blah.’ And so there's this very weird need to connect those landscapes to America's capacity to participate in war. And that was, yeah, I remember that was a piece of language that I really felt needed a new life.

VENUS WILLIAMS: When Morgan decided to include some of these photographs in the manuscript of her poem, she also decided to rewrite those image captions—you heard a few examples of these when she read earlier. And when she was rewriting those captions, she considered the following:

Saretta Morgan: Something that I think about with photographs that I encounter in a space like the FSA archive is the space between the subject and the person behind the camera and so I'm always looking for how the sitter, even if it's not a person, like how might the landscape be asserting itself against the intent of the person taking the photograph. And that's, you know, a purely speculative realm to be in.

VENUS WILLIAMS: Here’s another excerpt from “The Corpse at Stake was a Dream We Felt Inside Of.”

Saretta Morgan: Today was always that conjunctive type of country in which nothingness waits, structured in railroad traffic and black bottles to hold water without reflecting light. Among the terms necessary for life that may be commodified, water distinguishes itself through ease of portability, a particular ground, the dream chosen for its hills and perennial stream, knowing it happened and would happen again.

Its expatriated fish, their flat metallic bodies so colorful and love-making, simultaneously rearticulated the dream of a different face and body.

No one dreams their way out of a militarized landscape. Still, it's not a loveless task. The tongue moving vertically and vital to the war effort. Among the terms necessary, and often sobbing, we felt it to our bones.

–MUSIC–

VENUS WILLIAMS: “We felt it to our bones…” That last line from Morgan of feeling incursions on and to the water and the land, is an idea that infuses this next dialogue.

We’re going to stick to our theme of attachment. Specifically: human attachments to land. But we’re going to think about those attachments pretty expansively.

We’re going to talk about the act of moving through land; the colonial attachment to capturing that which can’t truly be captured; and what reimagining bodily attachments to land might look like, specifically in photography.

It’s heady stuff… but let’s get into it.

Kathryn Yusoff: I'm Kathryn Youssef. I'm a professor of Inhuman Geography in the School of Geography, Queen Mary University of London. And I'm author of A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None with University of Minnesota Press and Geologic Life in Human Intimacies and the Geophysics of Race.

David Alekhuogie: I'm David Alekhuogie. I'm a Los Angeles-based artist. And my work spans many different genres, I would say, but it has its kind of foundation in documentary photography, the history of documentary photography.

For me, landscape was probably what got me most interested in fine art photography. There was a specific exhibition that I saw at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art called, “New Topographics.”

VENUS WILLIAMS: “New Topographics” is a term that was coined in the 1970s. It defines a new approach to photographing the landscape—one that moves away from traditional ideas of natural beauty and wilderness and toward the things that photographers like Timothy O’Sullivan and Ansel Adams might have left outside the frame. Things like housing developments, gas stations, office parks, power plants.

Most importantly: the images are sort of boring. They’re not visually spectacular or dynamic. But they look at the landscape as it actually existed at that time.

David Alekhuogie: And I saw the work of Robert Adams, and I also came across a body of work called Summer Nights, Walking.

VENUS WILLIAMS: This is a series by Robert Adams published in 1985 documenting a suburban Colorado town at night.

David Alekhuogie: And that kind of like spawned this interest in walking, moving through space as a sort of political activity.

I found myself moving through the city, specifically, like, Los Angeles, trying to make photographs that spoke to me in meaningful ways. And one of the things that I became interested in is this idea that as a person moving through any sort of like shared space, you're supposed to be going from one place to another whether you're going from school to work, whether you're going from home to the gym, what have you, you should be moving through space with some sort of purpose. And that to me felt like a betrayal of free movement. If you didn't have anywhere to be, then you were suspect, you know, and I found that to be, as like a Black male, 20-something individual, you know, where not having, like, a place to be specifically, maybe brought upon feelings of unease or danger to people.

And so landscape, walking, the sort of politics of movement, urban space, all became somewhat early interests in my work, and they've become, like, recurring interests in my work. Probably more so now as I sort of become, like, more interested in post colonial theory, the history of colonialism. And using documentary strategies that facilitate decolonizing principles for people in marginalized spaces.

And for me, I started to think of those strategies as oftentimes performative, because oftentimes, the way you're viewed is out of your control. So through the way you perform in any given scenario, you're able to resist becoming a thing in any given moment.

So, yeah, I, I feel like that kind of gets a little bit closer to how I think about the body and landscape and how that has become a sort of politicized tool.

Kathryn Yusoff: I think it's really interesting what you're saying, David, around the sort of modes of capture, of loitering, of what it means to be in space and have space and have a geography and that not be a problematic but a kind of space of emergence and possibility.

David Alekhuogie: Right. One of the things that has been really interesting to me recently. Well, this kind of whole idea of the explorer, the myth of the explorer. This is kind of tightly connected to the history of photography. A lot of the sort of like early landscape photography is through the lens of the explorer as hero.

And then also just like landscape photography in the entire sphere of not only art photography, but photography in general is somewhat depoliticized. Like one of the things that was really interesting to me about the history of landscape painting was this connection to spirituality, which felt suspiciously pure in some way.

And I had started to sort of like reverse engineer this kind of idea of the sort of explorer hero in the sort of modern sense. And this is kind of more in my recent, interest in landscape and hiking culture, backpacking culture.

And so I actually read your book on a hike through Santa Catalina Island, which was, originally colonized by the Spanish, and this kind of idea of extending the sort of capitalistic freedom that you have.

Right? Like, you have like your home where you're at and you put everything in your backpack to go to another point, it's kind of like extending your home space. You know what I mean? In a similar way to where you would have like your home country and then you go to like another country, colonize that other country. It's like an extension of your freedom.

And I was trying to figure out the difference between someone who was just without a home, someone who was unhoused or just wandering, moving about and someone who has the sort of signifiers, the sort of like identity of like a through hiker. Because there's like a culture around it that is specific and aesthetic.

This idea of being able to explore, um, is like a part of American citizenship or is like a part of the expectations of like what it means to be in a sort of free society. And so, yeah, it was just something I was thinking about a lot on this hike through this island that was kind of like hiding its kind of colonial history, in many ways. When I would talk to people on trail, it seemed like they have like no, no real conception of that history.

Kathryn Yusoff: Yeah, I mean, that's exactly what kind of landscape photography did, is they emptied the landscape, right, of particularly indigenous presence, but it also kind of made a space to reimagine belonging and reimagine kind of attachment in those places. This is why this kind of term landscape for me as a geographer is problematic because it's sort of land and scape and it's very much configured in that idea of looking over space, but a very particular kind of colonial form of looking that seeks to capture and to possess and to, you know, make property of. And it's an interesting question to how you can embody those narratives of settler belonging, but also be aware of the forms of exclusion that they kind of map over.

David Alekhuogie: So land and scape. When you use those terms in that way, I start to think of this is a kind of psychological space. And when I first started to become interested in landscape as a possible genre for me to start to work in, I started to think of the body as a landscape, I started to think of it as like an arena where people had their specific agendas or aims that were oftentimes conflicting while at the same time, I often felt like there's this idea of landscape that to me is knowingly impossible. Or the brutality of colonialism comes from the sort of inability to capture in the absolute sense, the land or the landscape.

And how a person, place becomes like a thing. How to resist that, whether you need to resist that, whether the brutality itself is this kind of evidence of this kind of friction in that effort. And so, yeah, that has been tripping me up for a few days. Trying to have a thing that you can't really have, trying to own a thing that you can't really own, trying to possess something that you're unable to possess in the absolute sense and I'd just be curious to hear your thoughts on that.

Kathryn Yusoff: Yeah, I mean, I think It's also very much tied up in the kind of processes and narratives of race, so that what becomes a kind of question of mastery of earth also gets transferred onto racialized subjects and the making of racialized subjects.

And it's that kind of a question or impasse, of something that exceeds the possibility of capture becomes the kind of impetus to double down on those forms of capture in the same way that in colonial histories, the constant attempt to kind of resist and escape generates some of the regimes of violence. So I think that history of engagement with the earth and landscape through a kind of colonial, set of theories about the earth are very much in and tied to that space of conquest. I think something really interesting happens in terms of anti-colonial resistance and the kind of history of sort of being in an inhuman position as slavery is.

What people do within that space is to totally retool a relation to the inhuman. And I think, um, that to me is what is extraordinary about the thought that comes out of places like Martinique—Aimé Césaire, Frantz Fanon, Édouard Glissant—

VENUS WILLIAMS: —and Suzanne Césaire, who Saretta Morgan cited earlier. All of these folks are important, mid-20th-century post-colonial writers and thinkers from the famed French-Caribbean island.

But as Yusoff was saying…

Kathryn Yusoff: —that to me is what is extraordinary about the thought that comes out of places like Martinique, is understanding that in order to make a new language or a new kind of geopoetics that counters the sort of geopolitics of colonialism, there's a need to actually think with and in inhuman worlds and to kind of take the volcano as a journey fellow and the beach and the sea and the islands and the middle passage as a kind of part of how the colonial subject becomes, so part of its kind of material history, but also the possibility of making decolonial futures.

VENUS WILLIAMS: Think back to that excerpt we read from Suzanne Césaire’s “The Malaise of a Civilization,” and her call to imagine, quote, “the long-lasting and fruitful harmony of humankind and soil.” This is what Yussoff is talking about here—what can come creatively and otherwise by relating to one’s land in this way.

Kathryn Yusoff: Because I'm interested in the language of geology, I think about kind of the fossilizing effects. And we can kind of think about colonial photography as kind of having a fossil effect.

For example, one of the photographic images that was produced by geologists,such as Lewis Agassiz, who was a professor at Harvard in the late 1900s, was It's about producing these genres of comparative anatomy and zoology that described and made a kind of discourse of racial difference and essentially white supremacy.

So the photographic practice there is instrumentalized in creating a fossilizing effect of kind of holding those things in. Whereas we might see other practices in the kind of Black radical tradition as creating a sort of aesthetics of disruption.

So one of the things that I look a lot at photographs around mine sites in the 1900s in the U.S. And they, often picture the owners of the mine. And in the background, there's persons designated as laborers, often in very disenfranchised conditions.

But they're often turning away from the camera. So there's a way in which that blur or that sort of turning away from this particular way of inscripting history also creates this minute moment of resistance and cuts into the way in which this process of extraction has been narrated as building America.

So I think those kinds of ways in which we can see the tension between the intention of kind of colonial fossilizing forces which are trying to hold people in certain understandings of the narrative of race, and the way in which there's these kinds of rewritings of space, even if it's through a kind of blur and the turning away from the camera’s record. And you kind of see it in the archive in lots of different ways in which there's a kind of interference that produce the idea of and and the kind of existence of another world.

VENUS WILLIAMS: There are ways in which Alekhuogie’s work produces this effect, too. Specifically, a series of photographs called to live & die in LA. The images are twice and sometimes even thrice made, in a sense. First, Alekhuogie takes a photo of a waistline, where, in most cases, you see three slightly blurred bands of material and color: a t-shirt or bare Black skin; the waistline of the model’s pants or shorts; and, in between, the waistline of their boxers or briefs, suggesting the kind of horizon line one might see cutting through an Instagram-worthy sunset.

Alekhuogie then photographs his photographs at specific sites around Los Angeles. He then photographs some of those resulting images a third time in places of personal significance, like his mother’s garden. At each of these last two stages, Alekhuogie allows different kinds of local flora to enter the frame, along with the light and shadows he encounters at each place. The “residue” of place, as he calls it.

The title of each photograph illuminates these locations. Titles like: Avalon and 116th, Mom’s Garden; or Firestation 30, Mom’s Garden.

And for some further context: The corner of Avalon Boulevard and East 116th Street in L.A. is where police pulled over a 21-year-old Marquette Frye in August 1965—an encounter that escalated into a confrontation, which sparked what’s known as the Watts Rebellion, a week of civil unrest.

Fire station 30 is also in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles. It was the first of two all-Black fire stations in the city during the Jim Crow era when it opened in 1924. It’s now the home of the African American Firefighter Museum.

Alekhuogie’s titles provide the geographic coordinates for these locations, too.

David Alekhuogie: The idea of to live & die in LA, you know, I mean, it's a reference to a Tupac song, you know, that is like about, for me, the melancholy of being in existence in your body, in your place for better or worse. And to me that like felt like this incredibly radical idea.

So to describe the photographs, one of my students called them belt lines, because they sort of start with this idea of the body in its kind of most vulnerable state. So I have been thinking about the vital organs, the torso, the midsection, the lower back, these places also where someone might hide weapons. And this kind of history of, sagging culture, which like people have tons and tons and tons of ideas around, whether it comes from prison industrial complex, whether it comes from the sort of like fashion around missized clothes with this idea of boys trying to wear the clothes of men.

There's kind of a lot of theories around like, where this aesthetic takes shape like historically, but what I was most interested in is where a person's eyes could potentially fall compositionally just like as a kind of formal question. This idea of horizon to me is about thinking through a space kind of as a factor of time. You know, it's like the horizon line for me in a landscape points to distance in space, like how long it would take you to move from point A to point B. And so using the horizon as a kind of focal point for me was like a temporal strategy for like thinking about the space of the body, you know, as well as this kind of like push and pull of being consumed by the landscape, but also trying to impose your will on the landscape as well.

VENUS WILLIAMS: What results is a collaboration between body and place. Because in Alekhuogie’s photographs, the beltline is the horizon; and the body is the land on which local flora can bloom. But in this project, the body also becomes a politically codified territory.

David Alekhuogie: So this is an example of like resisting what it means to have one's like body be victim to the consequence of all of what it means to be existing Black outside in the nineties with, LAPD, even from like now. And the sort of joy of that the melancholy of that.

And so that work was for me about being at peace with being consumed and seen and objectified in very real ways and that there's a sort of push and pull in regards to that. And this idea of black masculinity as like a landscape for me felt like a psychological space that politically at the time,

VENUS WILLIAMS: That time being 2017, when Alekhuogie started making some related works in a series called “Pull Up.”

David Alekhuogie: It was during a time when Barack Obama's presidency was wrapping up and there was all of these questions around men needing to sort of like perform in space and a specific way to be taken in non-threatening ways. And I saw that task of like cutting your hair a certain way, pulling up your pants a certain way, doing this or doing that, as like a kind of band aid to a much larger issue around combating people's ideas around like what it meant to be, you know, Black and masculine presenting. And that also is kind of mirroring the city itself, and like how that had a real traumatic impact on me.

Like when I made that work, I had had interactions with the police that were life threatening that I thought that I would never have. Because I consider myself an artist and academic and so in a lot of ways, I had gotten into this space of thinking of myself as advocating for people who looked like me, but weren't me. And so being sort of like thrust into that real time was somewhat jarring.

And so, yeah, I think the work is both about me, I consider it a self-portrait, but it is also attempting to kind of unpack this idea of Black masculinity in space as a sort of uncomfortable, political, but also like emotional and it’s sexual and all of these kind of things that to me it feels wrapped up in conquest.

Kathryn Yusoff: Yeah. A lot of my empirical work is around the South in Alabama around mining and the convict lease system. And that's, you know, I mean, at its most basic form, it's a way in which Black masculinity of young men and boys was codified as a way to depopulate space, to remove people from place and place them underground in mines while actually doing this clearance of space, of black ownership of land and of voting rights and so on.

So it has those questions around sort of movement in space and freedom and I think there's a there's a incredible vulnerability in your photographs that give us other routes into a kind of geography of passion for inhuman places and things, which really resonates, I think, with those histories, in the U.S.

VENUS WILLIAMS: For Yusoff, Alekhuogie’s photographs also evoke a framework she uses to contextualize environmental racism—and the ways that governments and industries perpetuate past colonial ills by putting certain communities in harm’s way.

Kathryn Yusoff: We can think about this sort of general idea that geology is flesh as a way to understand our bodies as implicated in earth systems, in light, in heat, and implicated in processes of extraction and kind of weaponization of geology that are disproportionately borne of people of color. And we can think about even heat burdens in LA and tree coverage in the context of climate change, for example.

The intimacy of geology for me runs through mineral molecules of bodies. But also in terms of how toxic residues of chemicals and heavy metals and so on congeal around certain kind of spaces that are often in relation to racialized communities but also epigenetic forms of geologic stress that leave their geochemical signatures on bones and on bodies.

So we can kind of think about how geology builds bodies, but also how it takes them apart. That's what sort of comes to mind for me around thinking with that concept of the flesh of geology alongside David's photographs is just how we can tell other stories and other narratives around what it means to kind of be in place and to understand a different sensual logic of place as a kind of possibility and an opening to other place relations.

David Alekhuogie: I think of this idea of the geopoetic, you know is for me a psychic exercise, you know? I want to build new relationships to the histories that we already have, as well as finding opportunities to augment those histories in ways that point to maybe not more fruitful futures, but at least futures that feel inclusive, futures that feel somewhat authentic, if not true.

And I mean, one of the things that I've been, I've been thinking about during this entire conversation was just the effects of this global health crisis and how that has had an outsized effect on marginalized communities, just in the sort of like social hierarchy that people exist, the types of jobs that people have, like why they have to work those jobs and how they are a part of that, like capitalistic structure that facilitates how we all share space. Those things to me are quite sobering because it's like, I'm dealing with health issues, I have a lot of peers who are dealing with health issues and like, who even knows, you know, how much of that is dictated by how we have to kind of like show up as like individuals.

It's like an unanswerable, unknowable kind of a question. But for me, it's about storytelling. And I think, like, that feels the most readily available and the most useful.

—

VENUS WILLIAMS: Here are two final excerpts from Saretta Morgan’s poem, “The Corpse at Stake was a Dream We Felt Inside Of:”

Saretta Morgan: From the beginning the state was enchanted with us, in its strictly perverse way. The consequences were tenderizing. Structured in thick air and money. With a disgust for what was fleshy yet unuseful, our environment extruded life from surrounding terms. Physical development of this came bearing no scent or desire to harbor inside of.

In the beginning we said yes to the threshold we were meant to live inside of. At times we would be elsewhere still saying yes. Yes, dredge the river. Yes, mountain with clarity. Yes, be impassable. Yes, with different faces and bodies. Yes, turn us over.

—

Among terms necessary for life, proliferating streams, the question running versus organic disruptions of order. Exhausted, our tongues ordered against flesh, called to beauty in that particular way.

That dream wasn't ever a strategy, but thick red sun coming up over the territory, its light dripping from the corners of a stranger's exquisite face.

VENUS WILLIAMS: Thank you Saretta Morgan, Kathryn Yusoff, and David Alekhuogie. Morgan read from her poem, “The Corpse at Stake was a Dream We Felt Inside Of,” which appears in Widening the Lens, a publication from Carnegie Museum of Art. Morgan’s collection Alt-Nature is published by Coffee House Press.

Yusoff is the author of A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None, from University of Minnesota Press, and Geologic Life: Inhuman Intimacies and the Geophysics of Race, from Duke University Press.

You can explore Alekhuogie’s photo series “To Live and Die in L.A.” and other examples of his work online at davidalekhuogie—that’s A-L-E-K-H-U-O-G-I-E—.com.

In this episode, you also heard a brief excerpt from Suzanne Césaire’s essay, “The Malaise of a Civilization,” which appears in the collection The Great Camouflage: Writings of Dissent, translated by Keith L. Walker and published by Wesleyan University Press.

Widening the Lens: Photography, Ecology, and the Contemporary Landscape is a production of the Hillman Photography Initiative at Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh. For more information on the people and ideas featured in this episode, please visit carnegieart.org/podcast.

I’m Venus Williams. Thanks for listening.

###